At upcoming community stakeholder meetings to help develop that plan, a neutral party will be moderating the sessions, underlining strained relations between county entities and calls for more collaboration.

“Real collaboration matters. True, authentic collaboration,” said Montgomery County Probate Court Judge David Brannon.

Some of those groups recently sat down with the Dayton Daily News to talk about the discontent between the county and Montgomery County ADAMHS, including where this crisis services model originated, what potentially went wrong during the buildout since it was proposed, and where the county is going from here.

“The loss of crisis services evoked very strong reactions. But all of the parties involved are working together to bring ideas and solutions to the table,” said Sarah Hackenbracht, president and CEO of the Greater Dayton Area Hospital Association.

Where the crisis services model originated

In February 2020, the federal Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) released national guidelines on crisis care for behavioral health.

“It was the best, state-of-the-art, evidence-based practice to serve our community,” said Helen Jones-Kelley, executive director of Montgomery County ADAMHS.

The guidelines included the three-tiered model, which includes a hotline for people to call when they are having a mental health crisis, community-based mental health crisis response teams, and a place for people to go for help without crowding area emergency rooms.

RI International was one of the case studies featured SAMHSA’s national guidelines for behavioral health crisis services.

RI International’s crisis recovery center model first included a living room style, 23-hour temporary treatment center before combining it with direct access to its own emergency department in the form of a sub-acute crisis program.

ADAMHS partners with RI

Montgomery County ADAMHS would later partner with RI International after the release of SAMHSA’s crisis care guidelines, modeling the county’s crisis services after RI International’s center.

They were not required to put out an RFP, Jones-Kelley said. An RFP, or request for proposals, is when an organization solicits proposals from outside vendors where the vendors explain how they can meet the organization’s needs.

Montgomery County ADAMHS researched and met with the different providers, and they also hosted community meetings, which were held over Zoom at that time due to the pandemic, Jones-Kelley said.

“We do think we did our due diligence,” Jones-Kelley said.

In previous years, Samaritan Behavioral Health had contracted with Montgomery County ADAMHS to take crisis care calls, but they, and other local entities, lacked the capacity ADAMHS was looking for, Jones-Kelley said.

The crisis receiving center

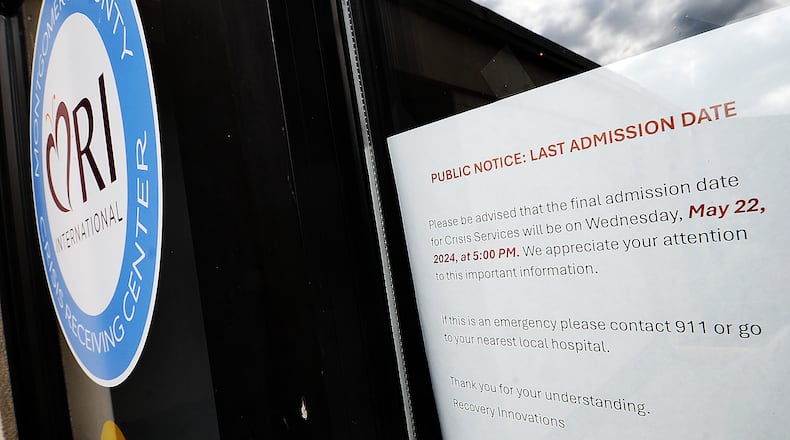

While there were complaints about the competing crisis phone numbers ― Crisis Now, which was partially funded by grant dollars, versus 988, which received federal startup funds at the state level ― much of the discontent appears to center largely on the Montgomery County Crisis Receiving Center.

“We were told from the beginning it was supposed to be a 72-hour crisis receiving center, and it never came to that,” said Butler Twp. Police Chief John Porter, who is vice president of the Miami Valley Association of Police Chiefs.

The Montgomery County Crisis Receiving Center was supposed to have a 23-hour observation area with recliners, along with a short-term psychiatric area with beds for people who need to be hospitalized on a 72-hour hold.

“This was supposed to help relieve the burden of law enforcement officers on the road, relieve the burden of the jail taking crisis individuals and relieve the burden of the hospital emergency room, and we never saw all of that come together,” Porter said.

Community partners have been working toward crisis services for years, with Hackenbracht calling the formation of OneFifteen — an addiction treatment provider that opened in 2019 — a win for those with substance use disorders. The community wanted to see something similar for mental health.

“What had unified partners previously was a shared goal of ensuring individuals are connected to the right treatment and services at the right time,” Hackenbracht said. “The concept of a crisis stabilization center or crisis receiving center was a shared goal. Unfortunately, we have not been successful in meeting that objective.”

The original vision of the center never fully came to fruition following lengthy discourse on where to put it.

“It took them a while to get launched, longer than any of us would have anticipated, but the pandemic played a lot into that,” Jones-Kelley said.

The 72-hour hold aspect was not part of the vision for phase one of the stabilization center project, Jones-Kelley said.

“Phase one was getting the observation unit in place. Phase two, because it was going to be even costlier, was going to come after,” Jones-Kelley said. “And the biggest obstacle with the location they landed in was space.”

One of the previous locations under consideration would have provided RI International with additional space above the observation area in order to put in beds for the 72-hold area, which would have been set up more like a residential unit, Jones-Kelley said.

RI International and ADAMHS originally wanted to put the crisis receiving center at the former AAA building at 825 S. Ludlow St., but the Dayton Board of Zoning Appeals denied a variance request in March 2022.

With the location at 601 S. Edwin C. Moses Blvd., RI International would have had to lease additional space to build out the 72-hour hold area.

“The zoning should have been ironed out before any agreements were done,” Brannon said.

While there is a lingering perception in the community that public funds were spent on the center itself, Montgomery County ADAMHS says no public funds were used for capital costs for the center, such as for purchases or leasing.

“We only pay for services rendered,” Jones-Kelley said.

Between 2022 and 2024, approximately $3.6 million in human services levy dollars were used to fund those direct services, according to ADAMHS records.

The rest of the funds for services included about $1.3 million in state allocated funds from Ohio MHAS and $1.8 million in federal funds, totaling approximately $6.7 million spent, according to Montgomery County ADAMHS records.

Where is the county going now

Montgomery County ADAMHS will be holding public meetings, with both in-person and virtual options, to take input for an RFP process for new crisis services.

“We welcome all to participate in these community meetings as we learn from each other how best to provide crisis mental health services to the most vulnerable citizens of Montgomery County,” Jones-Kelley said.

It is not clear if all three services will be replaced or just some of them. ADAMHS board members expressed interest in sticking with 988 as a crisis line to reduce competing crisis numbers.

“We are continuing to work with our hospitals, ADAMHS and all community partners as ADAMHS prepares for listening sessions with the public, community partners and stakeholders,” Hackenbracht said.

The Montgomery County Association of Police Chiefs said their goal was not to seem like it was their association against ADAMHS.

“Our goal here is in this specific arena with mental health services is having that voice and addressing those concerns as as our officers are active with them on a daily basis,” said Vandalia Chief of Police Kurt Althouse.

Details for the meetings are as follows:

- June 24 at 5:30 p.m. at Woodbourne Library, 6060 Far Hills Ave. in Centerville.

- June 25 at 1 p.m. at the Montgomery County Business Solutions Center, 1435 Cincinnati St. in Dayton.

- June 27 at 9 a.m. at the Montgomery County Employment Opportunity Center, 4303 West Third St. in Dayton.

Scott McGohan, former CEO of McGohan Brabender, will moderate the community meetings.

If you or someone you know is experiencing a mental health emergency, please call 988.

About the Author